“Stop calling it home!” my ate yelled at me during one car ride with my parents.“Why can’t I call it home?” I inquired. “Because we live in America, not in the Philippines… So stop calling it ‘home’!”

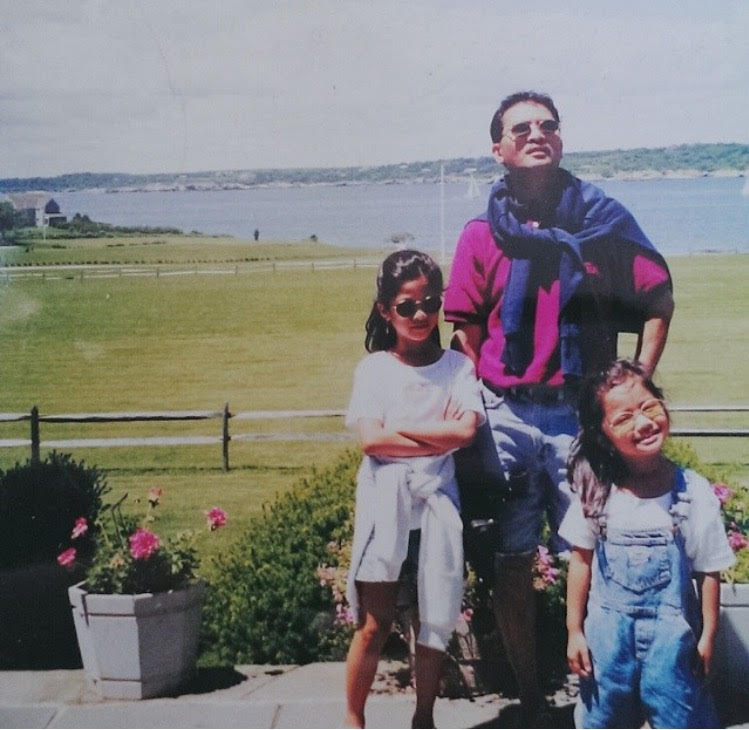

She is right, on a technicality. She has far more claim to calling the Philippines “home” than I do. Out of my family of four, I am the only one with birthright citizenship, a true blood “American”. My sister and my parents are all naturalized citizens; all born in the Philippines. They can all speak Tagalog fluently, meanwhile I still sound awful with my diction, pronouncing every syllable with an obvious American twang. I am far removed from this country called the Philippines, so why insist on calling the Philippines “home”?Where is “home” for me? At first, I picked up the euphemism from my parents; I figured it was just easier to say that we were going “back home” rather than going through the process of explaining to people that I was going to the Philippines, then having to explain all the different places I would have to visit. It was the one phrase that conveyed the message efficiently. This “euphemism” became more problematic the more I started to discover who I am as a person.

Even though I am American, and I was born in America, there has always been a weird gap between the American “me” and the Filipino “me”. Growing up in the American school system had made this gap apparent; I was simultaneously American but foreign. I was not white or black or Hispanic; I was clearly this “other”. This status of being “other”, or being just thrown under the category of “Asian” led to many days where people would make fun of me, and even assume I was some other Asian ethnicity. This has led to more “me love you long time jokes” and Chinese takeout jokes than I could possibly recount. This ridicule only deepened this gap within me. What is this being? Who am I? And how can I claim a country that I’ve never lived in longer than a family vacation, a language I barely understand outside of the basic “what time is it” and “where’s the bathroom”, and a culture that vastly differs from the “American” way of life? I enjoy the relative independence and freedom of a normal American 20-something, but my actions and my principles are heavily influenced from my God-fearing, Roman Catholic parents. I may not totally agree with their stances on issues such as abortion or politics, but they taught me how to stand up for myself, to be proud of who I am, and to be a person whose words could be trusted by others. Still, this musing does not address the question of why I refer to the Philippines as “home”.

I was clearly this "other"

This euphemism of “going home” stopped being a euphemism for me during my last visit to the Philippines. Unaccompanied by adults for the first time, and in the company of my closely aged cousins, we embarked on adventures in Makati, Manila, and beyond. It was during those late night drives, the sleepovers, and the conversations about life for them amongst bottles of Corona Light and gentle guitars that the meaning of “home” became apparent to me. What I was looking for, all those years when I felt a separation of self, between my citizenship and my skin, was something deeper than my American passport. I was looking for a heritage to call my own, something that transcended the physicality of my nationality and hid within my veins and my soul. I was looking for a culture I could be proud of, and a culture that I could pass down to my children. Something that my cousins have a direct connection to and an understanding of that I could only fathom in dreams.

The history of America, I have decided, is not the story I want to pass down to my children. I know they will have to learn American history in school, but they will get an alternate history at home. I will teach my children about the genocides and the suffering of the Native Americans and the Lumad, the destruction of precious resources, the occupation of lands far, far away, and the militarization of our own soil; things they will never hear at school. I rather retell the stories of struggle against political tyranny, the unification amidst political upheaval, and the hopes for a better country. I want to tell them the stories about their grandfather, who was at the Plaza Miranda at the beginning of martial law and marched on EDSA Boulevard as he faced down a tank with his sister right beside him as the people ended martial law. I want to tell them the stories of the sacrifices that both of their grandmothers had to go through in order to support their families in the Philippines. I want to tell them about how their aunt escaped a military uprising by being smuggled out of Manila by a brave uncle. I want to show them the dances and the songs that not even 333 years of Spanish colonization and subsequent occupations by the Japanese and the Americans could destroy. I want them to try balut (but they do not have to like it), drink soda from a plastic bag, and enjoy the culinary treats that only the Philippines can offer. I will tell them how their father and I were both activists, each in our own right, fighting for an independent, free Philippines.

When I refer to the Philippines, it will be referred to as “home”. My physical home may be in the United States, but “home” for me will always be the birthplace of my heritage, my birthright as a Filipina-American, and the place where my narrative begins: the Philippines.