Note from the Editor: In addition to being a staff writer, Kathryn Jan Estavillo, is also one of UniPro’s interns for the fall. As part of Fil-Am History Month, interns explored California’s new law to include history on Fil-Am farm workers and their efforts in the state’s education curriculum. Read on to see Kathryn's thoughts on labor leader, Pete Velasco.

Little to almost nothing can be found about his past. The names of his parents or any siblings he may have had remain unaddressed, unexcavated by both print and online sources. However, the amount of information that can be gleaned about his childhood, scant and insignificant, is a deceitful indicator of the great impact he left on the Fil-Am community. Peter G. Velasco, more commonly known as Pete Velasco, was born in 1910 in Asingan, Philippines. Having migrated to Los Angeles in 1931, Pete Velasco was a manong. Awarded to older male family members, manong is a term of endearment and respect familiar to many Pilipinos. Possibly an older brother, probably an older cousin, Velasco may have very well been given this title from birth. However, in between the 1930s and 1940s, the word adapted a new meaning, referring to the thousands of Pilipino immigrants, Velasco among them, driven by hopes of education and advancement to the United States.

While in the United States, Velasco worked in area restaurants for ten years, a challenging feat considering the American backlash directed towards immigrants, specifically Pilipinos. Despite America’s anti-immigrant mentality, Velasco stood as a representation of patriotism, fighting for the United States on European fronts during World War II and becoming an American citizen shortly after. Although his wartime service and citizenship are notable strides for Pilipino immigrants, it was his time as a farm worker that solidified his footprint in both Pilipino and American history. During the twenty years after the war, Pete Velasco worked on small farms in the Coachella Valley and Delano, California. There he, alongside thousands of Pilipino and Mexican migrant workers, faced horrendous treatment. They endured long hours of hard labor, unsuitable living conditions and meager earnings; these subhuman conditions continued even after their service expired. No longer needed and thus unemployed, former workers received no insurance. Their former employers for whom these immigrant workers toiled, exploited and maltreated, gave no help and showed no mercy. Velasco, along with fellow Pilipino farm workers Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, noticed this injustice and, together, they founded the Agricultural Farm Workers Association Committee (AFWOC) in order to address it.

The three leaders unified the Pilipino migrant workers under a common sense of rage and disempowerment and, on September 8, 1965 they initiated the Delano Grape Strike. This was a series of peaceful protests against California grape growers that lasted five years. Not long after the strike began, in 1966, the objectives of the Pilipino farm workers gained notoriety in the eyes of Hispanic civil rights leader Cesar Chavez as goals both the Pilipinos and Mexicans had in common. This led to the collaboration of Pilipino and Chicano farmworkers in the United Farm Workers of America. Aside from organizing the strike with Vera Cruz and Itliong, Velasco raised the money needed to launch the strike effort. By passing out pamphlets in front of supermarkets and other areas of congregation, he introduced the plight of migrant farm workers into public conversation. He was also more directly involved, arranging food caravans and establishing food banks for the strikers. He would later become a member of the union’s executive board and was elected as secretary-treasurer in 1980. Not only a supporter, Pete Velasco was familiar with the grit and grim, the suffering and sacrifice of the labor movement. As a member of this generation of Pilipino immigrant farm workers campaigning for justice, won his title as a Delano Manong.

There are many reasons why learning about Pete Velasco is important for Americans. Velasco was a piece of a larger puzzle, a representation of the effort to rectify the unforgivable conditions immigrant workers faced. By learning about Velasco, we acknowledge not only his role in the movement but we realize there may have been others whose efforts may have gone unnoticed. Additionally, Velasco is a canvas depicting American error. Velasco was one of many who traveled to the United States in pursuit of the American dream: education, opportunity, a better standard of living for himself, his family and the family he had yet to start. Velasco saw all these possibilities promised to him in the vibrant hues of the American flag. But what did he meet with? What did he and immigrants like him face when they set foot onto the shores of America? Unfortunately, this wave of immigrants, like many others, had racial slurs and undesirable jobs to look forward to. America boasts itself to be the land of opportunity, a country who begs for “your tired, your hungry and your poor,” a nation whose diversity is its most valuable asset. Still, this gross injustice in our history shows us what mentalities to avoid in order to maintain the true meaning of the United States, a lesson that needs, desperately, to be relearned today.

Undoubtedly, Velasco is an important figure in American history but, more so, in Fil-Am history. The Agricultural Workers’ Movement, the momentous step towards improving American labor, is recognized primarily as a Mexican or Chicano movement. However, Pilipinos played an enormous role. They began the movement but because Cesar Chavez was appointed director and Larry Itliong assistant director. However, Pilipino migrant workers received less attention than those of Mexican descent. The Pilipino leader of this major civil rights labor movement accepted a secondary role and the union organizing efforts of the Pilipinos in the US have been virtually forgotten. When researching the United Farm Workers of America or the Delano Grape Strike, the majority of articles one finds highlights the Mexican-American struggle with only a slight mention, a small blurb about the Pilipino role. Pilipinos have left footprints on the sands of American history and they are often unacknowledged. As Fil-Ams, it is our responsibility to ourselves if not to the general public to point out these footprints.

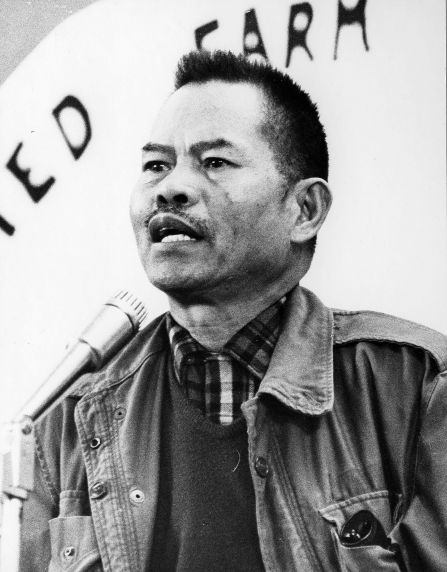

Photo Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library Website