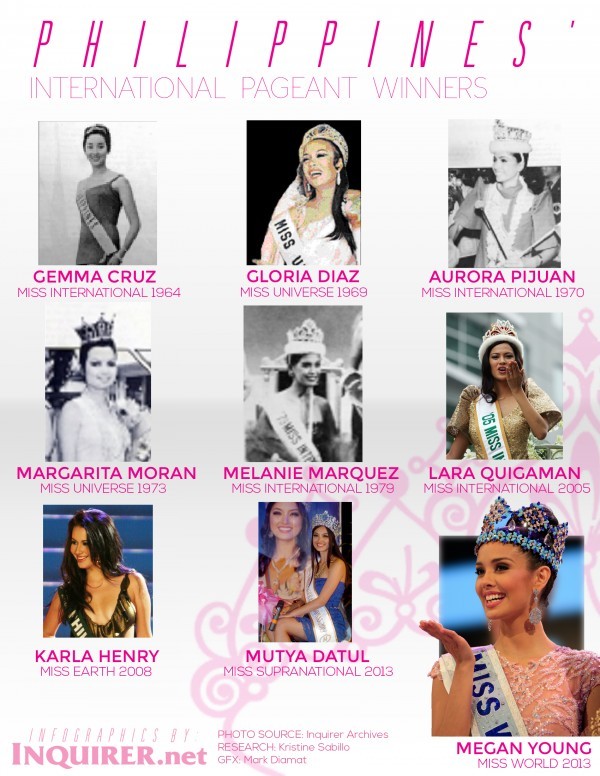

Pilipino beauty pageant winners dominated 2013. The year closed with a total of four winning titles for the country: Miss World, Tourism International, Miss Supranational, Miss International, and also a top 5 placement in Miss Universe. As the only country to hold titles in the top 5 international beauty competitions, it is safe to say the Philippines excels at the sport of pageantry. The country dotes on its queens and ties pride for the Philippines to each crown. Online we witness explosions of excitement when Ms. Philippines wins, and outbursts of rage when Ms. Philippines leaves empty handed.

I'm no anomaly to the Philippines' beauty pageant phenomenon. I have acted as host, producer, and stagehand for pageants and even competed in two myself. You get sucked in by the glamour of it all: buying gowns and strutting the runway, showcasing talents and eloquence, hearing cheers for your name and being asked for your photograph. There is nothing quite like the audience of a beauty pageant, however. The crowd emulates insane sports fandom with big signs, competitive spirit, and loud roaring cheers.

From international stages to local functions abroad, why are Pilipinos drawn to beauty pageants? Let's take a look at some contributing factors, including nationalism, willing ignorance, and the desire to prove something of the Philippines.

And we'll show the world What a country girl can change And we'll show the whole wide world That we have a pretty face Pretty face, pretty face, pretty face have we

Above are lyrics from "Pretty Face" sung by the Imelda Marcos character in the musical Here Lies Love. The former first lady immediately comes to mind when considering pageants, as she won beauty queen titles herself and earned nicknames like the "Rose of Tacloban" and "Muse of Manila." The song champions Imelda's infamous beautification program and vain pursuits. The 1976 Miss Universe competition, hosted by the Philippines, functioned as an opportunity to show off a developing nation deserving respect. Families in slums consequently faced eviction from their homes to hide poverty from the national image.

Even after the Marcos regime during the Philippines-hosted 1994 Miss Universe, police rounded up 270 street children to improve Manila's appearance. In Sarah Benet-Weiser's The Most Beautiful Girl in the World: Beauty Pageants and National Identity, Edgardo Angara, the Senate President at the time, voiced resistance:

"The Miss Universe contest is a misuse and abuse of our women that panders to the most ignoble instincts of our people."

Gel Santos-Relos, anchor of TFC's "Balitang America" (who actually hosted one of my pageants) echoed similar sentiments in Asian Journal while pondering pageant fervor:

"During these collective experiences, all of us are 'Filipinos,' regardless of our political leanings or social standing. We root for our kababayan candidates, athletes or favorite lead character in the teleseryes. We laugh, cry and cheer together. The unchanged 7.6 percent unemployment rate, rising gas prices, or another impending government shutdown do not seem to matter at all during that brief period."

Pageants are a way to pacify the people. The elaborate productions and beautiful women bearing the Philippines' name are welcome distractions to ongoing national crises. Santos-Relos also touches on one of three factors fueling pageant obsession: sosyalan. Rick Bonus in Locating Filipino Americans writes that socializing and celebrating pride during pageants are a way to bring communities together (especially abroad). The two other factors he notes are damay, or commiseration, and bayanihan, or communal unity.

Damay refers to the charity agenda most Fil-Am pageants have, since they tend to be fundraisers for an organization or cause with native roots. Damay is the motivating factor for purchasing tickets that reel in attendees. Bayanihan refers to the act of producing the pageant. It is usually a side project for community organizers that provides a way to collaborate with other Pilipinos.

Bonus takes a step further with pageants' allure by claiming they uplift Filipino American community. Often, pageants will include cultural segments wherein contestants sing tagalog songs or dance traditional dances in native dress. Participants, often second generation Filipino Americans, use pageants as an effort to relate to their roots. As a member of the Filipino American Community of Los Angeles (FACLA) stated in Bonus's book:

"[Pageants] are ways to announce to our community and the world that we are also achievers, even if many think that we are nobodies."

Clearly, to Pilipinos, a beauty pageant doesn't merely give one woman the title. The moment she gets her sash and crown, an entire nationality basks in the glitter of success–no matter how superficial.

Photo Credit: The Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, Binibining Pilipinas, Khaleej Times, Filipiknow.net, and amywillerton.blogspot.com

Photo Credit: The Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, Binibining Pilipinas, Khaleej Times, Filipiknow.net, and amywillerton.blogspot.com