The below submission is one of future stories to be told under the #AmIFilAm blog series.

Inspired by our past blog series #FKEDUP, UniPro wants to delve deeper into identity struggles that all Filipinos face in the community. We want to challenge what it means to be Filipino and to encourage readers to contribute their unique qualities to shape the idea of Filipino identity. The series is intended to discover how you value yourself as an individual and how you value yourself within the Filipino community.

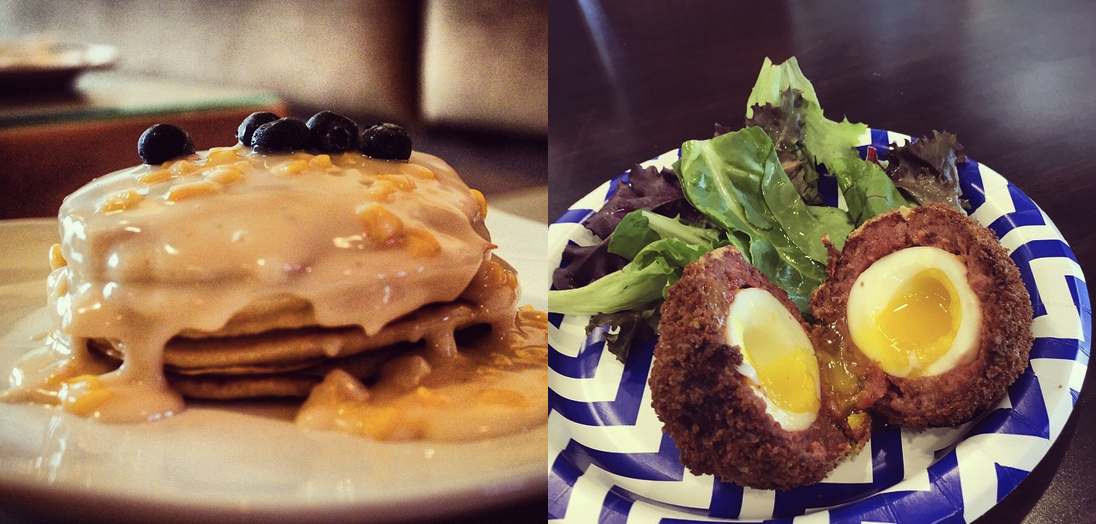

When I was growing up, I never saw it as a big deal that my parents were from different countries; it was just a fact of life. The privilege of growing up in New York City meant that more often than not, my friends’ parents were immigrants like mine. Everyone had weird food, so it wasn’t like my butter and sugar sandwiches were that much out of place, and all of my friends’ parents sent their kids to Catholic school, so we all wore the same ugly plaid jumpers.

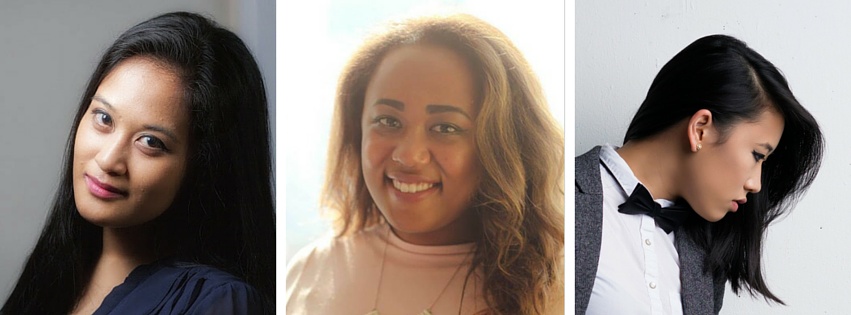

What did stick out was that my parents didn’t “match”—as an interracial couple in the 80s and 90s, my Filipina mother and Haitian father made a striking picture walking down the street. They didn’t think of themselves as vanguards though; it was more important to them that their children grew up to be American, and to be fiercely proud of themselves. We grew up eating lambi and kaldereta at the same dinner table, just another day in the life of the Chrispin family.

I only became acutely aware of my unique upbringing when I went to college. Not like I went far—oh no, this native-born New Yorker was much too cosmopolitan to abandon her hometown for somewhere as exotic as the Midwest. But my first few months at Fordham University brought with it a varied onslaught of microaggressions that I’d never encountered before:

“Where are you from? No, really from?”

“Wow, I thought you were [insert random country of choice]. You’re so exotic.”

[After touching me without my permission] “Your hair is softer than I thought it’d be.”

“That’s a crazy mix! How did your parents even meet, aren’t Haiti and the Philippines on other sides of the globe?”

“Did you pick a side? Like are you more Haitian or more Filipino?”

Of course, I met these queries and comments with the appropriate levels of side-eye, snark, and long suffering sighs. You can only politely demure so many times, murmuring,

“Oh thank you, yes my heritage is pretty unusual. My parents met at work, haha—my mom is a nurse and dad’s a doctor, so it was meant to be!”

It got to a point where my ethnic background became my default answer for ice breakers, since being mixed automatically solicited oohs and ahhs from the room.

These sorts of encounters weren’t isolated to my white classmates, either. Fordham’s black students were few and far between, with fellow Caribbean-Americans rarer still. When I did hang out with them, I felt like an imposter, since my experience of growing up a multi-cultural mixed girl in New York City didn’t match up with their experience raised as Black Americans; it felt like they were speaking in code.

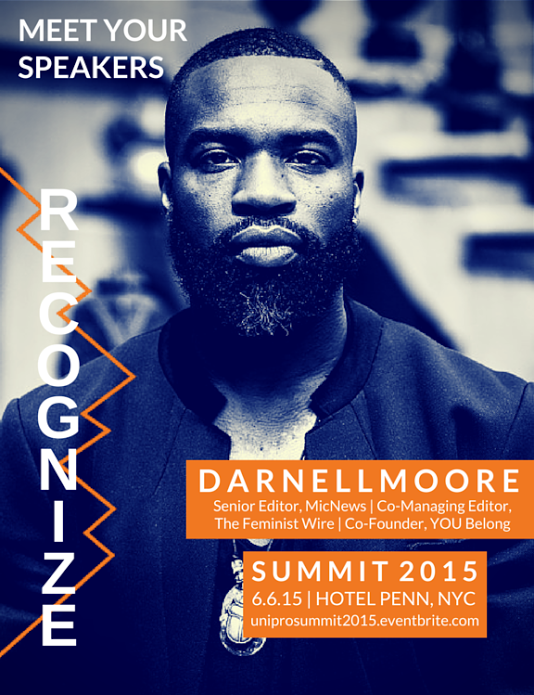

Funny enough, I felt most at home when I found Fordham’s Philippine American Club (FUPAC). Being mixed was less of an issue, especially since I wasn’t the only hapa[1] there. I also never felt the cultural dissonance that arose when I was in Black-identified spaces—the shared experience of being a second generation Filipino American were strong enough to bond me with my other Fil-Am classmates despite only having one Filipino parent. The cultural club let me explore my identity as a Filipina-American without discounting my mixed heritage by providing safe spaces for learning and community building.

The Bayanihan spirit is distinctly Filipino in its all-encompassing welcome—

for me, it was never an issue of “how Filipino are you;”

if you identify with Filipinos, you are Filipino.

As a diasporic people, Filipinos manage to maintain their bayanihan[2] even when living in foreign lands or marrying outside their culture. Only a heritage that is flexible and resilient could survive waves of colonization and coerced assimilation to retain its collective spirit across the globe! My experiences with FUPAC would be the catalyst for my work with the Fil-Am community—I always feel welcome in Pinoy spaces, and I seek to extend this communal spirit to other mixed Filipino Americans.

I’m proud to be a Haitian-Filipina-American, and hope to pay it forward to my kababayans[3] through UniPro and other means of serving my Filipino-American community.

[1] Being of mixed race

[2] Tagalog for community

[3] Tagalog for fellow Filipinos